Reshaping the Landscape of the Afterlife: "Sketching That Head, and the Stories of Its Body - Hsu Che-Yu Solo Exhibition"

Trans|張新

"The phenomenological 'becoming aware' of the body has turned into the uncanny: the production of the double, the membra disjecta, the fantasy of suffocation tied to the fear of being buried alive, and the split into two of the ego, which no longer gathers its organs together but looks at them as though from outside." - Rosalind E. Krauss [1]

How can we represent reality in the contemporary world, where the excess of images in the media and the overabundance of composite images have blurred the line between reality and fiction? What is the relation of violence, death, and darkness to reality? How can we reconstruct a "crime scene"? Or invoke memories unstable and irregular like the land and shatter the illusion of continuous memory (the media and history)?

With the endless barrage of media images, a damp, vague, dejected, weary, and ominous sensation lurks beneath the surface of our times. Wars, pandemics, and planetary crises today are mostly mediated by the media. We seek out different "mediums" (from news media to the metaverse) to "represent" reality as best as we can, but are confronted with the dilemma of media "representation" being always "a distortion of reality."

The media landscape has also undergone significant changes recently. While the mass media once played a substantial role in shaping our memories, the emergence of social media platforms has undermined our ability to construct “collective memories.” We have lost our common ground, as tribes are becoming insulated thanks to big data analytics. If, in the age of television, our memories had more or less been based on a shared foundation, then online platforms today have deprived us of this foundation, compensating for it only with what they provide, and we are left with fragmentary memories that are dispersed, ambivalent, and irreconcilable (truth is irrelevant, efficacy is everything).

Memory and Forgetting in Media Representation

Having lived through the transition from the “age of television" to the “age of computers,” I have noticed how our collective memories have rapidly been erased and forgotten. We continue to externalize our memories (writing, uploading posts and photos, and producing news stories) and contribute to the process of forgetting. Plato once wrote about the paradox of the relationship between writing and forgetting. Nowadays, it is the relationship between "representation" and "forgetting" that is amplified. Representation and forgetting are frenetically intertwined with each other; it seems that we have documented everything, but nothing is actually remembered. How can we overcome this paradox and restore our memories?

Ever since the radical deconstruction of "reality" by the postmodernist movement, we have been trapped in the realm of relativism: nothing is real anymore; we are left with infinite simulations and "representation after representation after representation..." (e.g., the cycle in which we take a picture of a living cat, upload it, and reproduce it in the real world). To confront this dilemma and tackle the problem of “post-truth” exacerbated by the rise of internet platforms, I wish to reaffirm the importance of “alternative truths”; alternative truth no longer asserts that “reality is superior to fiction”; instead, it stands in relation to “fictional” feelings such as affect, death, noise, impurities, unstableness, the uncanny, and impossibilities — fragmentary and dismembered realities: posthuman techniques of affect movement.

Brief Notes on the Exhibition Scene

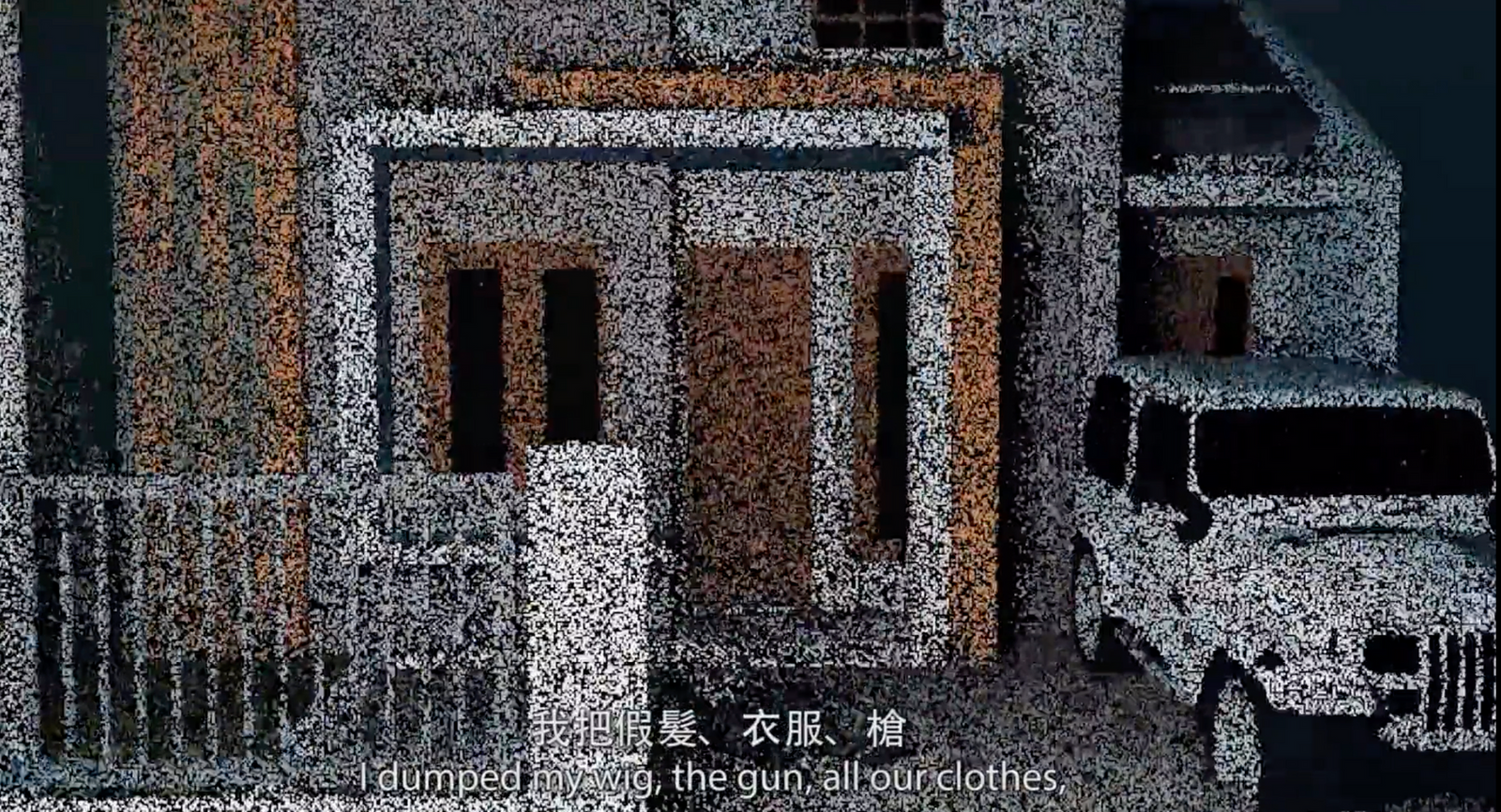

The camera cuts to the exhibition "Sketching That Head, and the Stories of Its Body - Hsu Che-Yu Solo Exhibition," a collaboration between artist Hsu Che-Yu and writer Chen Wan-Yin. As we enter the dark exhibition space, we are greeted with a screening of The Making of Crime Scenes; large-scale, coarse 3D model images, somber, desolate wuxia film sequences, and casual scenes in a karaoke bar meet us head-on. Soft cushions on the floor hint at a laid-back viewing experience, but the images displayed are hardly laid-back or heartwarming; instead, it is an act of remembrance filled with brutality, darkness, and fissures.

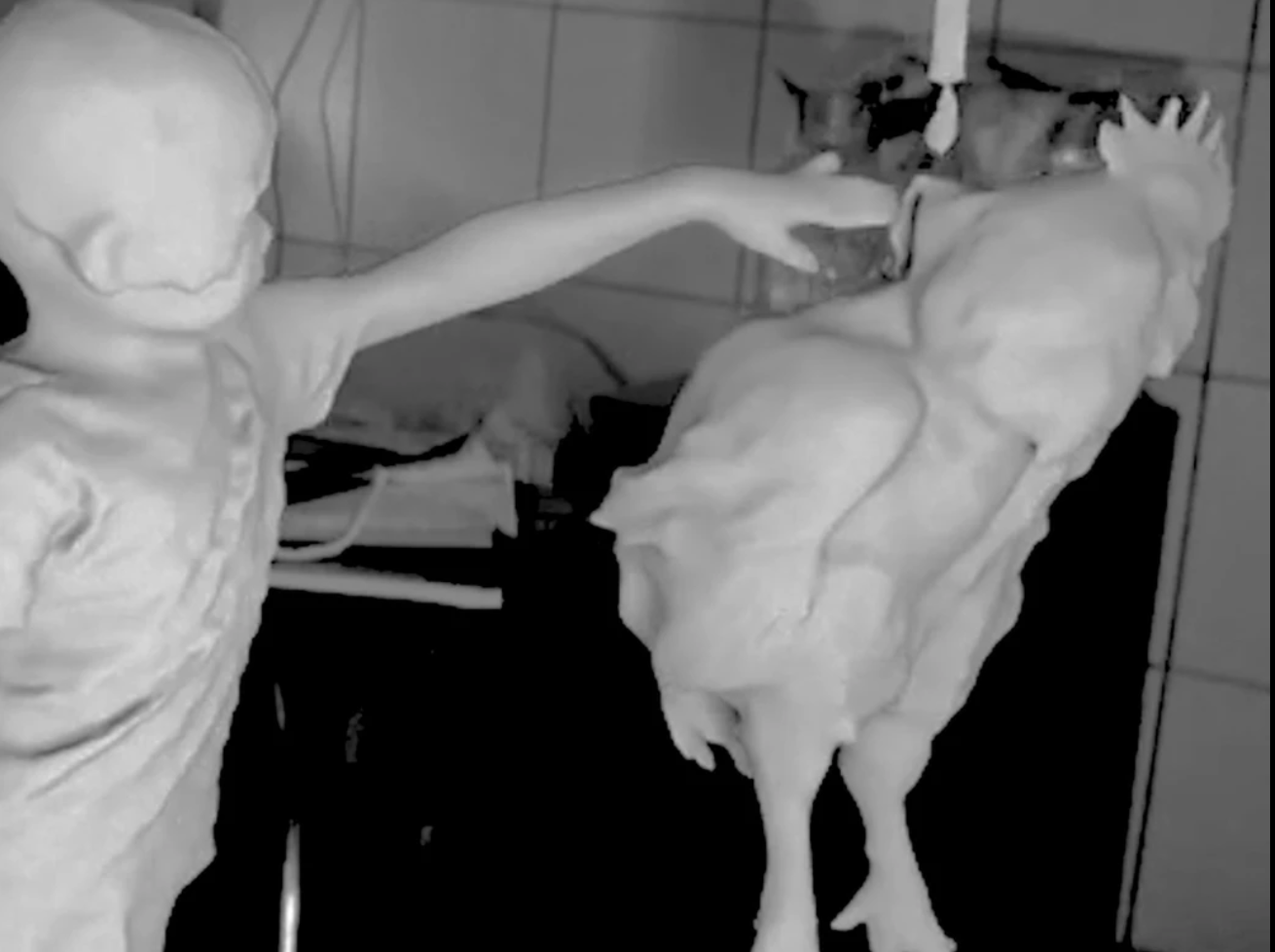

We turn left and enter the next room, which showcases the work Lacuna. A whispering, bleak, and dark narrative sweeps over us, with hand-drawn human figures pasted onto realistic settings; scratch, distortion, eyeball movements, and idle chit-chat take the protagonist's nerdiness to the extreme, accompanied by unsteady handheld shots from private home movies. Ominous intentions of murder lurk beneath the seemingly innocuous everyday conversations; heads detached from their bodies are inadvertently invoked in the narrative.

In the gray, dark space located further inside is a "material installation," the first work from the exhibition that is not a video projection: a gray severed leg leaning against the wall, a slanted television, and a vague, abstract picture painted in a gray-white hue. Reality seems to have been stripped of its colorful and alluring exterior, smeared over with a layer of gray with a suspenseful, fragile, and broken tone.

At the farthest end of the exhibition space, we see Rabbit 314; its intense, eerie rabbit images of terrible clarity strike us in the face: a rabbit's corpse performs the movements of a living rabbit (scratching and licking its fur). As the puppeteer reenacts the rabbit's gestures, the camera draws closer to the dead rabbit's fur, inducing a sense of tactile-visual dizziness in the viewer; the rotten stench of death oozes out of the moving images, a striking example of synesthetic experience created by visual stimulus. On the other side of the room lies the distorted projection of The Unusual Death of a Mallard. Ducks, animals, and children wander through the physical environment with stunning verisimilitude; yet their scanned models on screen are imperfect, coarse images constantly breaking apart, metamorphosing, and displaying their flaws.

Filth and Fractal Surfaces

If the images of the mass media and historical representation (modeling) are primarily visual, like the impeccable, plastic skin of internet celebrities, the technological models in Hsu’s work are wrinkled, scarred, and mutilated, resembling geological landscapes with their ragged, rough, and fractured surfaces. If mass media content, official histories, and collective memories, as well as scientific records and criminal archives, are “Earth images” — the “Blue Marbles” of cleanliness and order — which are “observable and controllable”, “planetary images” move along the ground, infiltrating the muddy, filthy, damp, vague, and textile surface, which causes us to remember our daily lives in a completely different manner.

Bodies are no longer whole; they are severed and decapitated. The viewers, like detectives, gather hints in the exhibition rooms and actively piece together their own fabrications. We come to realize that the mass media, scientific specimens, criminal archives, and collective histories all seem to minimize the complexity of life. However, Hsu does not shy away from the mediums; instead, he manipulates them in a private and everyday fashion and is not afraid to expose his own position. [3]

The Collective and the Private: Entangled Geological Skins

As to self-disclosure and private sensibility, in the recounting of the assassination of Henry Liu in The Making of Crime Scenes, we not only see the assassinator, Wu Dun, enthusiastically reminisce, as well as the graphical modeling of his memories, but we also witness the artist interviewing a 3D scanning team in a karaoke lounge, and hearing them talk about how they perform forensic scanning at gruesome crime scenes. After the camera does a 360-degree survey of the lounge, we see him on stage ferociously singing the chorus of Dave Wang's "One Game, One Dream." [2] Coincidentally or not, in The Unusual Death of a Mallard, during a transition in which the camera pans over an uncanny coat of stain on the floor in a karaoke bar, the female protagonist is, similarly, singing A-mei's "Can't Cry It Out." The violence, trauma, and fissures concealed in our past intersect and intertwine in our collective memory of '90s pop music.

Hsu’s camera movement reconstructs the scenes as he transforms real-life scenarios into 3D models. In The Making of Crime Scenes, the artist abandons his trademark “handheld perspectives” (with its authentic home-movie texture) in favor of “non-human perspectives,” like model shots that continuously glide, scan, and reconstruct reality (even the camera movement of the live wuxia sequences look like 3D models). In the last shot, the floating, spectral perspective surveys the geological surfaces and brilliantly “penetrates” Wu Dun’s 3D-modeled head, blurring the line between the inside and the outside; we are no longer watching Wu Dun’s memories from the outside but seem to have folded into the narrator’s interior. The viewer is forced to wear the “skin mask” of the protagonist; our memories become entangled in the collective memory of wuxia movies, bloody news reports, and karaoke lounges.

Embracing the Afterlife! - Beyond the Representation of Nightmares

Our camera cuts back to the “alternative truths” mentioned earlier. While mediums, scanners, and modeling distort our reality, is it not better for us to take back the scanners instead of letting the media, private corporations, and ideologies control them and manipulate reality? To reconstruct our own models? To thrust the scanners inside Putin’s head? Or to “reduce” the clarity and integrity of the modeling? Why are we content to live in a tribalized present controlled by internet platforms, unwilling to quit and reactivate alternative collective memories offline?

Hsu often “shapes” his images into menacing, decadent, gloomy, violent, and sardonic compositions; he also aims to reconstruct the impossibility of “death” by inducing a liminal state that verges on the “afterlife.” What stops us from creating our own jovial, cheerful, crazy, divided, and chaotic models in order to take part in the afterlife? So let us gladly pledge alliance with the animals, skins, severed limbs, specters, digital noise, and festering geological pores of the planet! But don’t forget to stay close to the ground, as well as the interweaving hybridization of inverted realities and Mi Mi Mew Mew, because we still need to re-excavate the vestiges of our dark collective/private memories buried within our island strata, in order to receive the alternative truths of the afterlife.

Notes

[1] Bois, Yve-Alain, and Rosalind E. Krauss. Formless: A user's guide. New York: Zone Books, 1997, pp. 160-161.

[2] The song "One Game, One Dream" echoes Wu Dun's life experiences: the spectacle of life is but a game, a dream. But this does not mean that games and dreams are therefore fake; they are, to a certain degree, true in their own right.

[3] In his work, Hsu often reveals the "camera position," which makes the reenactments more "reflexive" and prevents them from reinforcing the inflexible historical narrative.

「現象書寫-視覺藝評」專案贊助單位:財團法人國家文化藝術基金會、文心藝術基金會