Amusing Ourselves (Not) to Death: Speculative Images of Braaainwashing

Trans|張新

Flat screens are flooded with information every day, all trying to influence us. They shock us, make us laugh, or want to go shopping, as they eagerly seek our attention. Fragmented messages on social media platforms like Instagram, Line, YouTube, and Facebook strive toward “affecting” us. They exploit the information anxiety of modern people, attempting to brainwash us, transform us, and make us different (usually by consuming things) — that’s right, this article you’re reading now is no exception.

In contrast to the plethora of sensational media content, fancy montages, and fast-paced editing that catch our attention, contemporary art often provides a place for contemplation, introspection, critique, and historical retrospection to engage in aesthetic contemplation that is free from information anxiety and constant acceleration. For instance, the video works of Chen Chieh-Jen, Tsai Ming-Liang, Yuan Goang-Ming, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Bill Viola all offer unique aesthetic experiences, employing long takes that are cold, slow-paced, and non-narrative to make us experience the force of the image itself.

However, a mixed visual language — the “Mi Mi Mew Mew Style” — has emerged recently in the art world with its constant transmutations. This type of visual language does not make the viewers sink into aesthetic contemplation; instead, it extensively uses fragmentary montage, nonsensical everyday narratives, and silly voices — with a distinctively nerdy, gamer spirit — to induce us into an uncertain state of dizziness, panic, and mental confusion. Indeed, we can no longer view these artworks from the perspective of aesthetic contemplation, but must learn to appreciate their cool and funny effects.

People in the contemporary art world often dismiss the “entertainment value” of artworks, believing that it is “merely the product of consumerism.” They criticize it with remarks such as, “How is that different from the sensory entertainment of YouTube videos?” or, “Am I watching an artwork? Or am I at an amusement park?” Preoccupied with major issues of geopolitics, identity, as well as national or historical trauma, they often think of artworks that employ superficial visual and audio effects as breezy and dismissible, whose only aim is to entertain people as opposed to shedding light on deeper, “structural issues.” One can say that a disorderly plaything like Mi Mi Mew Mew only puts people into a superficial state of memes, amusing them with spectacular effects, but is unable to make people stop and think seriously.

*A*

A floating head comes in at you in a dark space from all sides, blabbering about conspiracy theories, piecing together fake news from content farms in a moronic, lisping voice. As the virtual head speaks, it opens and closes its mouth in an exaggerated and frantic manner, making the entire head distort accordingly (the exaggerated movements of the mouth remind me of a Francis Bacon painting). We are dumbstruck by the maximal stimulation of memes cited all over the place. While this may be just another fictitious contemporary video artwork, it is also entirely realistic, given that our lives have been under the attack of “information” — information that we’re often unable to determine its authenticity — for many years now without ever a moment’s respite. You don’t believe this? You think this is ridiculous? Just open the phone you're holding in your hand and you'll find yourself caught in the endless universe of information flow :)

The "Reality Effect" of Images: Is It Real?

Video artworks force us to become reflexively aware of our bodies with their cold, reserved long takes. The viewers are no longer spectators watching safely from afar, but actively taking part in the artwork. In Hollywood movies, viewers are passive spectators, as their motionless bodies are dragged obediently into a “fantasy land.” In contrast, avant-garde artists or theater practitioners aim to challenge viewers by making it difficult for them to “empathize” with the work by employing various methods that foreground critically the subject of the “medium” itself, moving away from the "representation" of their contents. For instance, experimental cinema and expanded cinema (sculptural film) have utilized the reflexivity of the medium to make viewers reflect on the “cinema of cinema” as well as the material conditions that together make cinema possible — light, shadows, film, dark rooms, and machinery — rather than succumbing to the hegemony of the cinematic narrative.

However, in the genre of “essay film,” [1] local narratives are reintroduced into the artworks. As the postcolonial condition of globalization becomes an oft-addressed topic in contemporary art and film festivals, artists are also resisting traditional narrative structures with fragmentary, polyphonic, or meta-narratives. We can therefore observe the return to narrative structures in contemporary art and how images are becoming increasingly hybridized. [2]

Contemporary artists use images to free us from manipulative illusions and challenge us with “reality.” As art historian Claire Bishop states, because contemporary art stands against the society of the spectacle of consumerism and theater, its goal is, thus, to achieve the “reality effect.” [3] This aspiration is essential to art: to critique the spectacle and the hegemony and strive for reality. Likewise, these works seek to expand one's corporeal perception and refuse to offer visual illusions in which viewers can indulge themselves.

*B*

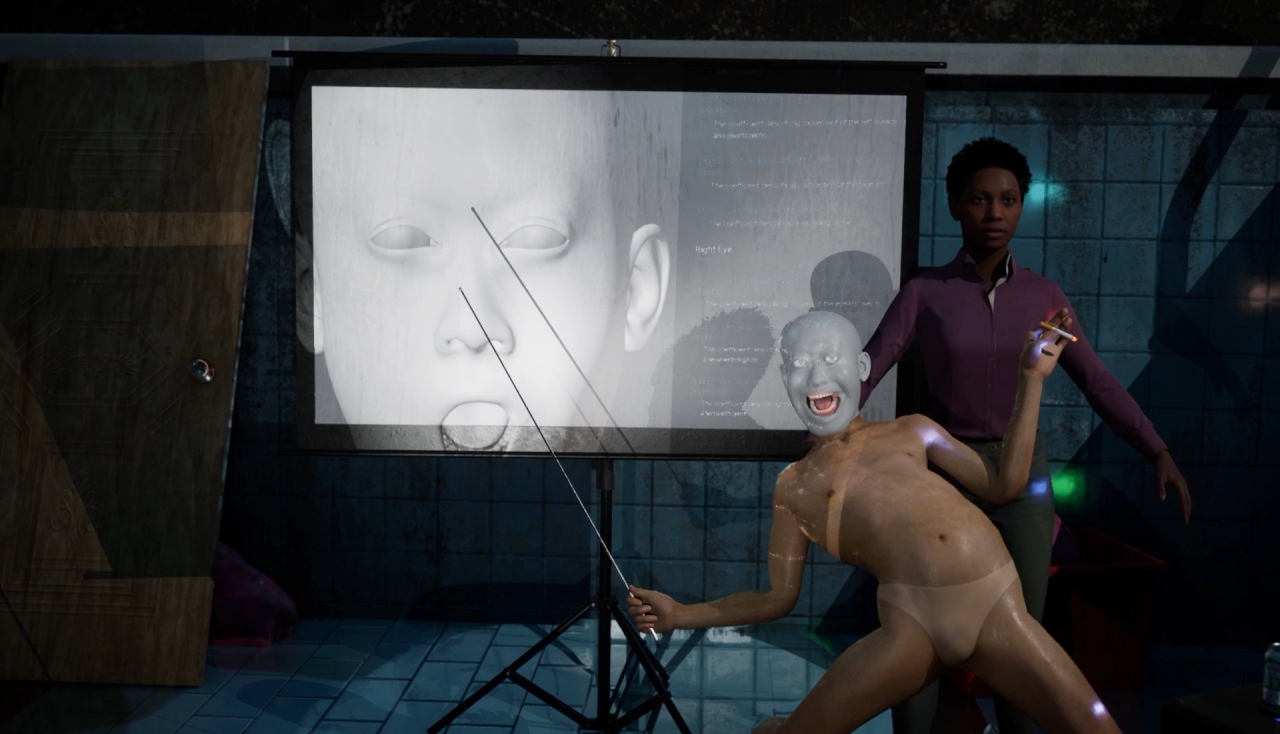

A figure with a slippery body babbles nonsense and about childhood memories, as well as how digital humans are made (they buy their heads on the internet). The digital puppet speaks with a cigarette in hand (the cigarette shape-shifting like magic), dances in the air, and rapidly twists, turns, and twitches its limbs. Like Deleuze's "body without organs," it appears to be unbounded by physical and institutional restrictions and has entered a state of formless emancipation.

As we’re lured by the digital puppet’s trash-talking, we notice that a few people dressed in green are controlling its body. The single-channel video can be roughly divided into three layers: the digital man analyzing the process by which digital humans are constructed (talking shit and reminiscing about how it had once dreamed about controlling robots as a child); revealing that the digital man is also controlled (the green men are uncovered); and finally, the stroke of genius, how this arrangement points to the fact that the viewers in front of the screen are also digital humans that are being controlled. We believe ourselves to be real, flesh-and-blood human subjects that possess free will, yet as big data and metaverses conquer the earth, have we not already become digital humans created from digital models?

Installations and the Corporeal Flâneur: (Static) Visibility and (Mobile) Tactility

Contemporary art is inseparable from the “body,” not so much the body image created by artists, but more the regulation of the “body of the viewer.” In the contemporary environment in which the immersive experience has gained prominence, artists have come to regard the viewer’s corporeal experience as part of their works. Instead of employing the spatial arrangements of a traditional movie theater or proscenium, they regulate the viewers’ bodies in the exhibition space to keep their bodies in motion and prevent them from watching performances behind a fourth wall. These artists make use of “installations” (in today’s world, photography, video art, and paintings all need to be “turned into installations”) to mobilize the viewer’s body; as the art historian Boris Groys suggests, the viewer’s body is transformed into a flâneur. [4]

Benjamin has also considered the question of the altered state of the viewer: in the age of mechanical production, the viewer is, more often than not, in a state of “distraction” rather than “concentration.” An example of this state of distraction is architecture: unlike the state of aesthetic contemplation where we appreciate the aura of a traditional painting, the distracted viewer is engaged in an interwoven experience with space, an experience connected to tactility and irreducible to its visual dimension. For instance, while you can easily reduce a building to its visual image through photography, when you walk into one, your experience of it is based more on the cumulative effect of the senses, namely tactility. In a similar fashion, Benjamin also highlights the importance of tactility in architecture: “for the tasks which face the human apparatus of perception at the turning points of history cannot be solved by optical means, that is, by contemplation, alone. They are mastered gradually by habit, under the guidance of tactile appropriation.” [5]

This is also why many contemporary video installations have abandoned the single-channel format, which allows the viewer to stop and concentrate, in favor of spatial installations and sound fields that activate the viewers’ physical sense and set their bodies in motion. No longer looking at the artworks passively, they must now actively move along the space, collecting the hints left inside the works to construct their own narratives like a detective at a crime scene.

The body has become the major battlefield of art. While traditional party-state politics manage our bodies through a top-down approach (the Big Brother, physical exercises, military training classes, flag-raising ceremonies, and pep talks), the neoliberalism of today opts for a more insidious approach to regulate our bodies comprehensively (what is the most fashionable hairstyle, clothes, outfit, the most trendy electronic device, the hottest video game, and the most Hito Steyerl artistic expression?).

As the hottest gaming experience infiltrates the exhibition space, some may believe that Mi Mi Mew Mew images are simply borrowing internet memes like “ready-mades” to defamiliarize the viewers (namely the elites and old folks), with little creative transformation. However, when great artists include ready-mades in their works, they not only transfer internet memes from the subculture to the exhibition space but also refer to the everyday political relations of “controlling-controlled,” demystifying these relations from the veil of consumerism to make them perceptible. Or, to put it differently, the work must reflexively consider this relation of mutual control and critically employ the techniques of control to which we have grown accustomed.

*C*

Six grotesquely shaped installations form a large stage; layers of torn, distorted, repulsive human bodies are projected onto it. A narrator is talking shit and dropping video game references, chattering about the associations and feelings that arise from ”colors.” The dazzling and flickering projection of the “Porygon scene” from Pokémon makes the situation even more psychedelic and dizzying. A small inconspicuous screen is hidden behind the large installation stage, showing a strange-bodied man playing with a projector. The projector is constantly changing the projected colors, which are precisely the colors cast on the stage with the six strange installations in the room.

The sensorial association of color reminds one of Derek Jarman’s Chroma, written before his death, but the colors here are further connected to the status effects of game characters (blue for frostbite! And the mad symbol of “death” is, too, always present in the work); the sickening installation mapping brings to mind Tony Oursler’s formless and multi-layered projection installations, with persistent trash talk added on top of it. The main narrative technique of the work is the random connection of homonyms, which reminds one of the fragmentary information sequences of the internet.

Meaningless prattle, meaningless repetitions, schizophrenia, and interminable hyperlinks present meaningful features, with their madness! This work is best “felt” rather than “comprehended.” An extremely moronic, chaotic, and brainless sensation washes over you and astonishes you. However, as you reach the back of the stage and discover the little green video screen, you realize that everything you’ve felt is the result of someone “controlling” the projection and that the viewer was also part of what was being “controlled.”

But isn't this state of being controlled similar to ours? Every day we encounter a real-world shaped by links that are repetitive and synonymous, full of emotional appeal, filled with cool and fancy words, and fragmentary (how many windows and hyperlinks have you opened while reading this article?). Now it is less about the rigor of rational thinking, but more about the ways of dramatic expression and its emotional effect. Not what is said, but "how you say it." Reason, logic, and inference are rendered moot; what's important is our feeling of "belief" and how the media manages it.

The Politics of Affect: "Controlling-Controlled"

Technologies of control manage our emotions by influencing, transforming, and brainwashing us. A simple glance at your social media platform, and you are overwhelmed by a deluge of things that are trying to affect you, things you can’t determine whether they’re fake or not. Contemporary art is a space that defies the consumerist society, a space for people to stop and think, a space of contemplation, critical reflection, and inner experience. However, as contemporary art today introduces “information flow and fragmentary experiences of the media,” should we create artworks that are more interactive and sensorially stimulating to make them more accessible to the public, simply because viewers nowadays have grown accustomed to the stimulation and interaction of social media?

Of course not! Mi Mi Mew Mew is not just about acrobatic, eye-catching effects. When referring to the ready-made experience of internet fragmentation, great works don’t just affirm or follow the trend without a second thought, nor do they simply deny and criticize it. Instead, they “over-affirm” it, accelerate it, run it wild, and push the sensory experience to the limit! In contrast to the negative critique of the status quo, the German media theorist Wolfgang Ullrich suggests that exaggeration is “a way to free humans from the fetters of particular frameworks of thought. It is a way for people to draw up theoretical structures, cast doubt on the legitimacy of ideologies, and promote a satirical attitude.” [6]

As the frenetic dance movements are pushed to the extreme, the over-stimulated viewer begins to reflect on the various absurdities of the internet that are taken for granted and develop an alternative and reflexive critical consciousness (which is different from critical thinking that is didactic and condescending). Furthermore, the meta-approach to camera movement allows viewers to become reflexively aware of their act of “seeing” rather than simply being immersed in the audio-visual experience.

On the subject of the nonsensical connection of fragmented trash talk, Neil "Post-man" criticizes in his book Amusing Ourselves to Death the fact that the information flow of the age of television consistently promotes the fragmentation of knowledge: "that television's conversations promote incoherence and triviality [...] Television, in other words, is transforming our culture into one vast arena for show business. It is entirely possible, of course, that in the end we shall find that delightful, and decide we like it just fine."[7] In contrast to the structurally rigorous discourse of written culture, television and today's internet tend to enforce fragmentary, meaningless, and superficial scenarios. We are transformed by the media into accepting emotionally stimulating entertainment and believe that the written words of rigorous thinking are old-fashioned and out of date.

Based on the varied nature of different mediums, Post-man considers "consumerist entertainment" (television performance) and "serious thinking" (written discourse) to be fundamentally incompatible, believing that we will lose the ability to think without a return to the written tradition. In comparison, Mi Mi Mew Mew operates according to a state of mutual infiltration instead of the logic of mutual exclusion — who's to say that we can't think with focus while distracting ourselves with entertainment?

We don't just amuse ourselves to death. When amusement is turned up to the max, we also begin to think reflexively about how we’re being controlled today and led more and more by superficial emotions. Of course, you can immerse yourself in excessive effects and become brainwashed by sound and light, yet the reflexivity of these artworks also points toward the interrelationship between the media and makes us reevaluate our digital-zombified daily lives.

Do U know? The future of digital z0mbies is upon us! W3're d1gital z0mbies an) th3 k1nd t#at's al1ve! H3h3h3

Notes

[1] Leading essay film artists include: Jean-Luc Godard, Harun Farocki, Chris Marker, and Hito Steyerl; Ho Tzu Nyen, Hsu Chia-Wei, and Liu Chuang also incorporate similar techniques in their work.

[2] 江凌青,《從雕塑電影邁向論文電影: 論動態影像藝術的敘事傾向》,《藝術學研究》第16期,2015,頁169-210。

[3] Claire Bishop,《畢沙普選輯1:表演與美術館》(黃亮融 譯),台北市:一行出版,2021,頁11。

[4] Boris Groys. Art Power. The MIT Press, 2013.P. 64.

[5] Walter Benjamin,《機械複製時代的藝術作品:班雅明精選集》(莊仲黎 譯),台北:商周出版,2019,頁56。

[6] Wolfgang Ullrich,《不只是消費:解構產品設計美學與消費社會的心理分析》(李昕彥 譯),台北:商周出版,2015,頁218。

[7] Nill Postman,《娛樂至死》(章艷 譯),桂林:廣西師範大學出版社,2009,頁72。

The works mentioned in this article are by the artist Li Yi-Fan:

A: Important_message.mp4 (2019)

B: HOW DO YOU TURN THIS ON (2021)

C: Boring Gray (2021)

「現象書寫-視覺藝評」專案贊助單位:財團法人國家文化藝術基金會、文心藝術基金會